- Depi nan Ginen bon Nèg ap ede Nèg!

- jafrikayiti@gmail.com

No to Organized Religion, It's Spirit that Counts

Testaman Liberal Yo: Verite osnon Malatchong?

February 19, 2022

Yon bon dechoukay nesesè pou Ayiti netralize tout malfèktè

March 13, 2022No to Organized Religion, It's Spirit that Counts

By Brian Stevens

Haitian Times Staff , Published in May 2000

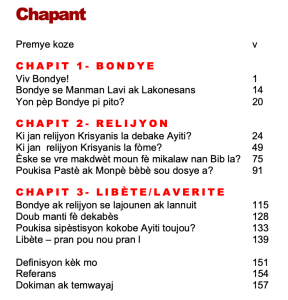

MIAMI – With the provocative title “Viv Bondye, Aba Relijyon” (Long live God, Down with Religion) it is no surprise the author Jafrikayiti wants to shake up the traditional take on spirituality and faith and reclaim a domain he says is dominated by those who use organized religion to divide.

“Intrinsically the Christian message is violent, ethnocentric and beyond hope for repair,” said Jean Elissaint Saint-Vil, who took the name Jafrikayiti as a pure representation of his Haitian-African identity and a rejection of the above traits. “This book is not a cry of rebellion, but rather the beginning of a search for the truth,” Jafrikayiti said as he described the deeply personal nature of his work. “It is a series of questions in my mind since I was young, questions that make up the essential elements of my faith.”

“Viv Bondye! Aba Relijyon!” – liv sa a disponib nan adrès sila a:

The son of an Episcopal Priest, Jafrikayiti, who was an altar boy in that same church, said his personal spirituality comes from “all the experiences I have had in my 33 years of life.” “My understanding of God,” he said, “is the understanding that She has put in to all human beings naturally, that sense of wonder that we know we cannot have created ourselves.”

As he puts his faith in a God whose Spirit is revealed in the hearts of men and women, Jafrikayiti dismisses the core Christian beliefs and organized religions as divisive and ethnocentric, hoping that Haitians who examine their spirituality will move beyond organized religion. “I really believe this is the time for this message to go out and be a catalyst for others to dig into these issues,” Jafrikayiti said. “This book is a tool for a reflection that has begun but is not yet finished.”

Truth be told, “Viv Bondye, Aba Relijyon” is- as its title suggests- more than just a tool for reflection. It is, in fact, a firm denunciation of organized religion, and a call for Haitians to reject Eurocentric ideas and organized religions in favor of embracing African traditions. “The Bible is racist and ethnocentric and beyond a doubt it is not talking about any one human family,” Jafrikayiti said. “The whole concept of Christianity divides people.” The new author’s critiques found mixed support among many Haitians, including one historian who took a more nuanced approach toward the role of organized religion in society.

Jean Claude Exulien, a history professor who is now with the Center of Information and Orientation, Inc. in Little Haiti said organized religions have had their low points in history, to be sure, but he would not dismiss organized religion’s ability to do good too. “Organized religion as practiced by the Catholic Church in 19th century Haiti didn’t do anything for the Haitian people,” Exulien said. “It was imposed on Haitians during two campaigns,” said Exulien, “first in 1894 and then again in 1943.” Exulien called the attempts to drive Haitians away from traditional African voodoo divisive and largely condemned the church for its efforts.

But at the same time though, Exulien said the church could not be dismissed completely for its past failings. “The Catholic Church used organized religion to play a positive role in the crisis of conscious of the late 80s that forced Duvalier out,” Exulien said, pointing to a period of aggressive Church leadership on human rights issues that began with a visit by Pope Jean Paul II to Haiti in 1982. Jafrikayiti does admit that while he is denying organized religion he does not deny the good works done by some within religious circles. “That is very true.

“Viv Bondye! Aba Relijyon!” – liv sa a disponib nan adrès sila a:

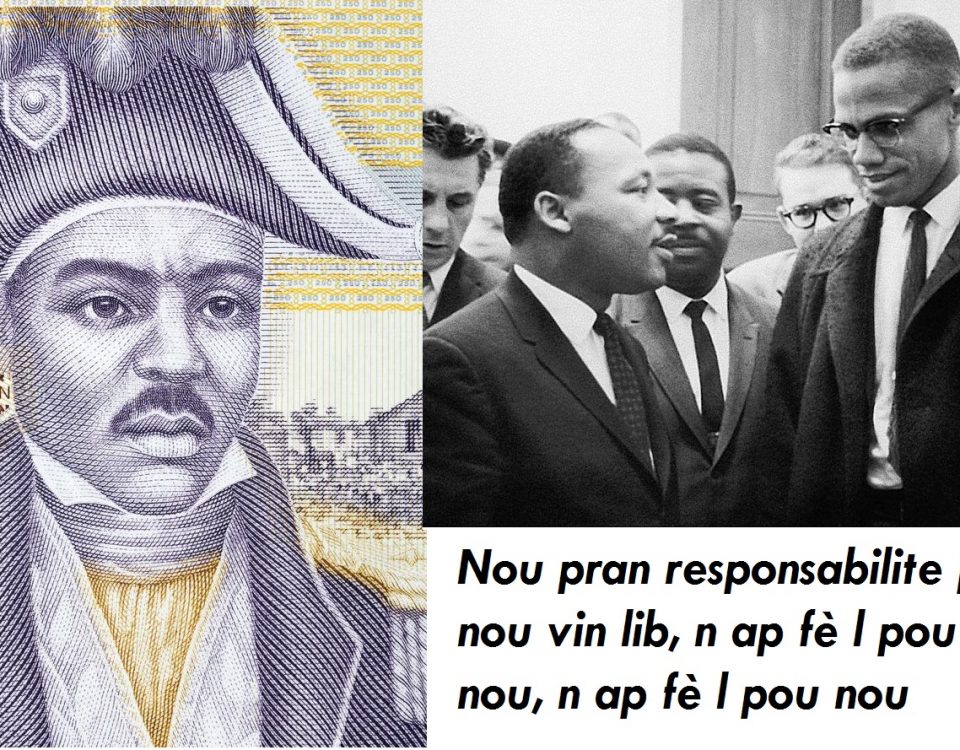

Many religious people do good, and that is one reason why organized religion survives,” he said, citing people like South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Mother Theresa and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “But look at the details,” Jafrikayiti warned, “and they show those who have done good encounter persecution at the hands of organized religion.” King’s ostracism from the Southern Baptist Convention because of his stand on civil rights, and his infamous Letter from a Birmingham Jail, serve as signs to Jafrikayiti that maybe even Dr. King recognized the limitations of organized religion. “Dr. King told us he is dissatisfied with the church and he thinks maybe organized religion is too bound to tradition and whiteness to be a liberation force for its people,” Jafrikayiti said of the letter.

In a Haitian context, Jafrikayiti points to the Rev. Edwin Parason, Haiti’s consul to the Dominican Republic, who stood up for the rights of Haitians working in the sub-humane conditions of the country’s sugar cane fields. “He didn’t find any support among the church in the Dominican Republic. And how about Titid’s relations with the Vatican,” Jafrikayiti added as two examples of religious institutions’ failure to stand on the moral high ground.

The author considers movements like the controversial liberation theology of the Catholic Church seen in Latin America as “one of the more humane faces of organized religion that can only serve to preserve it.” “But nothing could make organized religion in to a tool that is appropriate to the work of God and can teach man how to be fully human,” he added. Jafrikayiti said much of his efforts are an attempt to “demystify the Bible.” The author said the status of the Bible as a holy text makes people loathe to challenge it, even though historical evidence suggests the origins of the book are not what many would believe. “Do we see fingerprints of God or of people on the Bible,” he asked.

Jafrikayiti could not have chosen a subject more destined to raise the ire of his countrymen- except perhaps soccer or politics. Casual reactions to his first published work confirm that much. “He must be crazy,” said an elderly Haitian woman questioned by a visitor at Notre Dame d’ Haiti Catholic Church, Little Haiti’s largest house of worship. Sentiments among the clergy were along the same lines. “I’m sure it is full of theological errors,” a Miami-based priest said definitively and dismissively. “Don’t waste your time,” he said as if to add further council.

“Viv Bondye! Aba Relijyon!” – liv sa a disponib nan adrès sila a:

To a certain extent passionate reactions among fellow Haitians is exactly what Jafrikayiti is looking for, in hopes of raising a debate about the role of organized religion, long considered one of the most powerful forces in Haitian culture. “There is always hope,” he said of his struggle to unseat organized religion’s lock on God and spirituality. Jafrikayiti pointed to the trend away from organized religion in the last few decades, and toward a more personal spiritual approach to life.

“People are giving up on organized religion and at the same time understanding the need for God,” he said, adding “the end result will be people will recognize that God and organized religion are two distinct things that are totally opposite.” Jafrikayiti pointed to the environmental movement as evidence of a humanistic movement among people who he believes are beginning to realize “we are one human family.” “It’s going to happen,” he said of the move toward one human family. “Are we going to do it fast enough is the question,” Jafrikayiti asked. “As a global community are we going to wake up fast enough?”

1 Comment

ah & Jahes love beloved Jafrikayiti. Thank you for sharing this review of your wonderful book. I was sad when I first read the comment by that elder Haitian woman on the Corbett List Server circa 2000. She was so certain that she knew and understood religion more than you! She wanted to cut you off and put you down and that hurt me a lot. I feel that you wrote the book to help Haitian people discern between belief in a Good God/Goddess, the practice of a healthy spirituality versus religious doctrine. I don’t even think that she had read any part of the book, but she had an opinion, a very misguided one, that led her to rebuke your work. I loved reading every word of the book. And, I feel that it should be read over and over. I also know that Haitian churchgoers will learn a lot by reading the book. And, as a RastafarI I feel that your book opens up the opportunity for discussions about the meaning of God/Goddess and the importance of faith and spiritual practice. Still, I know that part of your motivation or inspiration might have been Liberation Theology as was promoted by the “Ti Legliz” movement in Ayiti when Jean Bertrand Aristide was campaigning for the first time in the early 1990s. There is much more that you can add to the book to make it more current, but it was a good way to engage folks in the process of decolonizing mentally and emotionally from Eurocentric models of being, loving, and believing. Blessed love. #Ayiti #1804 #vivbobndyeabarelijyon